How oft, in spirit, have I turned to thee,

O sylvan Wye! thou wanderer thro' the woods,

How often has my spirit turned to thee!

Tintern Abbey on the Wye

“No poem of mine was composed under circumstances more pleasant for me to remember than this. I began it upon leaving Tintern, after crossing the Wye, and concluded it just as I was entering Bristol in the evening, after a ramble of four or five days, with my Sister. Not a line of it was altered, and not any part of it written down till I reached Bristol. It was published almost immediately after in the little volume of which so much has been said in these Notes.”--(Wordsworth, The Lyrical Ballads, as first published at Bristol by Cottle.)

My concern here turns on the notion of a Philosophy of Nature, the Pantheism of the Romantics. As well, the discovery of the self, which is the subject of my Notes on Romanticism, Parts 1 and 2, on Goethe's Werther, now leads to the more ambitious subject of The Ego in Nature: “Are not the mountains, waves, and skies, a part / Of me and of my soul, as I of them?” Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, III, lxxv. Once again, the fundamental notion of nostalgia is central here, and particularly in its context as a re-visitation.

My concern is with the question of the relationship of the emancipated 'self' of the early Romantics and the relationship with "Nature" that was crafted onto it. Both are intimately related to one another in this discourse. In the poems of Hölderlin, for example, the self is directly reflected in Nature. Nature speaks of the absence in the poet's soul, the lack within his heart, after the gods have departed.

In Wordsworth, however, a more objective consideration of Nature begins to emerge. The Prelude is a well-known paean to the nature of the poet's homeland. But in 'Tintern Abbey,' Nature and the Gothic become the vehicles of nostalgia. And they are something else as well: they are a much needed refuge from the contemporary reality of the poet's life. The phenomenon that has come to be known as the 'industrial revolution' had unleashed a dramatic confrontation between man and Nature, where Nature came to be exploited for the sake of production determined by markets. In a whirlwind of change that began as far back as the seventeenth century, and first of all in England, not only was the economic and the social structure of the country forever changed, but its landscape as well underwent a process of transformation which is still visible in its scars and contrasts. Red brick factories rose next to Gothic church steeples in the hills and vales of England, canals cut through the fields, pits and mines were gouged out of the earth, and small towns invaded their surrounding farmlands, pitting and pocking the landscapes, a monstrously ugly process that was clearly visible during Wordsworth's life time.

The unstoppable dynamic of the industrial revolution moved to exploit the population of England no less ruthlessly than it did its landscape. In his early poems, Wordsworth had exposed the miserable lives of urban dwellers and of the children of the poor, as he became a notorious commentator on what was then known as the "condition of England question."

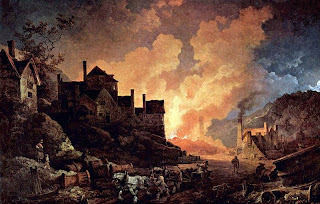

However, this was not going to be the tenor of the poem celebrating his return to Tintern Abbey. Wordsworth could not have expounded on nostalgia and past loves, on the search for absence, in such famous landscapes of the changing England of his own day, subject of so many discussions and parliamentary debates, such as the famous furnaces of the West Country, Coalbrookdale (Loutherbourg's painting of Coalbrookdale at night, 1801, below), the desolation of industrial landscapes (print of Lombe's silk mill at Derby, below), the iron bridges of the industrial revolution (cast iron bridge at Coalbrookdale, 1779, below), or the Birmingham canals. He chose instead, as he had to, the ruin of a Gothic Abbey, untouched in its green, sylvan, environment since the looting of the monasteries in the sixteenth century. This was required by his own intent at idealization, which is the underlying psychological mechanism of nostalgia.

Louthenbourg, Coalbrookdale, 1801

Lombe's Silk Mill (1719):

the most advanced factory in

the early eighteenth century

Coalbrookdale, Cast iron bridge built in 1779, considered a

Coalbrookdale, Cast iron bridge built in 1779, considered amarvel of engineering prowess at the time.

Preston Bridge with industrial landscape

in Lancashire

LINES, COMPOSED A FEW MILES ABOVE TINTERN ABBEY, ON REVISITING THE BANKS OF THE WYE DURING A TOUR. JULY 13, 1798

FIVE years have past; five summers, with the length

Of five long winters! and again I hear

These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs

With a soft inland murmur.--Once again

Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs,

That on a wild secluded scene impress

Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect

The landscape with the quiet of the sky.

The day is come when I again repose

Here, under this dark sycamore, and view

These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts,

Which at this season, with their unripe fruits,

Are clad in one green hue, and lose themselves

'Mid groves and copses. Once again I see

These hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines

Of sportive wood run wild: these pastoral farms,

Green to the very door; and wreaths of smoke

Sent up, in silence, from among the trees!

With some uncertain notice, as might seem

Of vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods,

Gainsborough, The Cottage Door, 1780

Or of some Hermit's cave, where by his fire

The Hermit sits alone. These beauteous forms,

Through a long absence, have not been to me

As is a landscape to a blind man's eye:

But oft, in lonely rooms, and 'mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind,

With tranquil restoration:--feelings too

Of unremembered pleasure: such, perhaps,

As have no slight or trivial influence

On that best portion of a good man's life,

His little, nameless, unremembered, acts

Of kindness and of love. Nor less, I trust,

To them I may have owed another gift,

Of aspect more sublime; that blessed mood,

In which the burthen of the mystery,

In which the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world,

Is lightened:--that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on,--

Until, the breath of this corporeal frame

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things.

Gainsborough, Landscape

1760

If this Be but a vain belief, yet, oh! how oft--

In darkness and amid the many shapes

Of joyless daylight; when the fretful stir

Unprofitable, and the fever of the world,

Have hung upon the beatings of my heart--

How oft, in spirit, have I turned to thee,

O sylvan Wye! thou wanderer thro' the woods,

How often has my spirit turned to thee!

And now, with gleams of half-extinguished thought,

With many recognitions dim and faint,

And somewhat of a sad perplexity,

The picture of the mind revives again:

While here I stand, not only with the sense

Of present pleasure, but with pleasing thoughts

That in this moment there is life and food

For future years. And so I dare to hope,

Though changed, no doubt, from what I was when first

I came among these hills; when like a roe

I bounded o'er the mountains, by the sides

Of the deep rivers, and the lonely streams,

Wherever nature led: more like a man

Flying from something that he dreads, than one

Who sought the thing he loved. For nature then

(The coarser pleasures of my boyish days,

And their glad animal movements all gone by)

To me was all in all.--I cannot paint

What then I was.

Gainsborough, The Marsham children 1787

The sounding cataract

Haunted me like a passion: the tall rock,

The mountain, and the deep and gloomy wood,

Their colors and their forms, were then to me

An appetite; a feeling and a love,

That had no need of a remoter charm,

By thought supplied, nor any interest

Unborrowed from the eye.--That time is past,

And all its aching joys are now no more,

And all its dizzy raptures. Not for this

Faint I, nor mourn nor murmur, other gifts

Have followed; for such loss, I would believe,

Abundant recompence. For I have learned

To look on nature, not as in the hour

Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes

The still, sad music of humanity,

Nor harsh nor grating, though of ample power

To chasten and subdue. And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man;

Gainsborough, Cornard Wood

1747

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things. Therefore am I still

A lover of the meadows and the woods,

And mountains; and of all that we behold

From this green earth; of all the mighty world

Of eye, and ear,--both what they half create,

And what perceive; well pleased to recognise

In nature and the language of the sense,

The anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse,

The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul

Of all my moral being. Nor perchance,

If I were not thus taught, should I the more

Suffer my genial spirits to decay:

For thou art with me here upon the banks

Of this fair river; thou my dearest Friend,

My dear, dear Friend; and in thy voice I catch

The language of my former heart, and read

My former pleasures in the shooting lights

Of thy wild eyes. Oh! yet a little while

May I behold in thee what I was once,

Gainsborough, Portrait of his daughters 1759

My dear, dear Sister! and this prayer I make,

Knowing that Nature never did betray

The heart that loved her; 'tis her privilege,

Through all the years of this our life, to lead

From joy to joy: for she can so inform

The mind that is within us, so impress

With quietness and beauty, and so feed

With lofty thoughts, that neither evil tongues,

Rash judgments, nor the sneers of selfish men,

Nor greetings where no kindness is, nor all

The dreary intercourse of daily life,

Shall e'er prevail against us, or disturb

Our cheerful faith, that all which we behold

Is full of blessings. Therefore let the moon

Shine on thee in thy solitary walk;

And let the misty mountain-winds be free

To blow against thee: and, in after years,

When these wild ecstasies shall be matured

Into a sober pleasure; when thy mind

Shall be a mansion for all lovely forms,

Thy memory be as a dwelling-place

For all sweet sounds and harmonies; oh! then,

If solitude, or fear, or pain, or grief,

Should be thy portion, with what healing thoughts

Of tender joy wilt thou remember me,

And these my exhortations! Nor, perchance--

If I should be where I no more can hear

Thy voice, nor catch from thy wild eyes these gleams

Of past existence--wilt thou then forget

That on the banks of this delightful stream

We stood together; and that I, so long

A worshipper of Nature, hither came

Unwearied in that service: rather say

With warmer love--oh! with far deeper zeal

Of holier love. Nor wilt thou then forget,

That after many wanderings, many years

Of absence, these steep woods and lofty cliffs,

And this green pastoral landscape, were to me

More dear, both for themselves and for thy sake!

1798.

Tintern Abbey

No comments:

Post a Comment