Items from the David M. Robinson Memorial Collection of Greek and Roman Antiquities

Portrait Bust of Agrippina the Elder

The Robinson Collection at the University of Mississippi Museum of Art, in Oxford, Mississippi

The University of Mississippi's Museum of Art has a site on the web:

This was my second visit to the University of Mississippi’s collection of Greek and Roman Antiquities collected, mostly at Olynthus, by David M. Robinson The previous Faulkner Conference I attended was in July 2011. The first reunion and meeting for the Conference always takes place at the Museum of Art. While waiting for someone to talk to, I paced the galleries and photographed the wonderful exhibits of the Robinson collection.

Just as I did five years ago, I visited the David M. Robinson Collection with great interest. The collection is only partially displayed at the main University Museum, the remaining part of the collection being housed at the Mary Buie Museum next door.

MUSEUM OF ART

The David M. Robinson Collection of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the University of Mississippi Museum of Art is one of the finest collections of its kind in the united States. Covering the period from 1500 BCE to 300 AD, the collection contains Greek and Roman Sculpture, Greek decorated pottery, architectural fragments, small artifacts in terracotta and bronze, and Greek and Roman coins.

The images shown here are photographs I took at the university of Mississippi Museum of Art in July, 2011, and July 2016. The bulk of the 2011 photographs are in my blog post pertaining to that trip. A few examples of black-figure and red-figure Attic pottery which are works of Athenian craftsmen from the sixth and fifth centuries BCE and part of the permanent collection. There are only a few pieces depicted in the blog, including ceramics from the Greek colonies in what is today southern Italy, but the few that are here reveal the main characteristics of each style of mainland Greek Art. As well, I show a few oil lamps, and the painting on a kylix which reveals an unusual method of depilation by means of the oil lamp.

[To enhance the size of the photos right click on them and open in new window]

Kylix depicting a woman removing her pubic hair by burning it with an oil lamp.

Oil lamps were also used for personal hygiene. On this Kylix (drinking cup), a woman is shown holding an oil lamp near her pubic region just close enough to singe the hair as she squats over a water basin with a sponge in her right hand as a precautionary measure. This practice was common for pubic depilation in Greece and its depiction on Grecian art is extremely rare. (Source: Museum notes).

OIL LAMPS

Oil Lamps were not only used for light but also

served as votive offerings in sanctuaries and also as tomb furniture. Lamp

forms are highly varied, ranging from simple to elaborate. Lamps used in

ancient Greece could sit on stands or be suspended from cords or chains. Olive

oil was a popular fuel and a wick would be placed in the lamp and out the

nozzle to ensure even burning. Lamps from Athens changed around the VIIth.

century BCE, with more shallow lamps and longer nozzles being made in molds.

This popular form was the standard for thousands of years. Larger and more

decorative lamps were specialty items and usually denote ceremonial status.

(Source: Museum notes)

On this occasion, the Museum also exhibited vast numbers of coins and medallions from the Classical period and part of the Robinson collection.

On this occasion, the Museum also exhibited vast numbers of coins and medallions from the Classical period and part of the Robinson collection.

The campus of the University of Mississippi in Oxford is dominated by groves of magnolia and crepe myrtle (lagerstroemia), which is in bloom in July.

Pink crepe myrtle

Jack Faulkner's home

The home above belonged to Jack Faulkner, brother of the author. It is now property of the University of Mississippi.

Walton-Young Mansion House

Museum Note: The photo (below) shows the Walton-Young Historic House, a registered Mississippi Landmark and a typical middle class home of the Victorian era. Horace H. Walton, who owned a hardware store on the Oxford Square, built the house in 1880. Walton and his wife, Lydia Lewis Walton, lived in the house with their three children: Lewis, Victoria, and Horace, until his death in 1891.

After Walton passed away, Lydia boarded university students in an upstairs bedroom to provide for her family. In 1895, she married Dr. Alfred Alexander Young, a country physician and widower from Como, Mississippi. Dr. Young moved into the house, bringing his son, Stark, and daughter, Julia.

Stark Young was the most famous resident of the Walton-Young house, and he remained there while attending Ole Miss at the turn of the century. Young became a well-known novelist and playwright.

Dr. and Mrs. Young lived in the house until their deaths in 1925. The First Presbyterian Church of Oxford purchased the house for use as a parsonage. Four ministers’ families occupied the house over the next fifty years.

The university purchased the house in 1974, and it housed the Center for the Study of Southern Culture and the Honors College. The house became a part of the University Museum in 1997.

The house is located at the corner of University Avenue and Fifth Street, adjacent to the University Museum. The house is currently closed to the public for renovations.

Please call 662.915.7073, or email museum@olemiss.edu for more information.

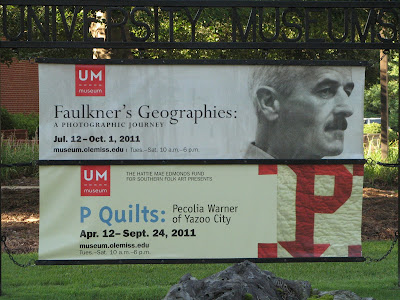

Museum of Art's Exhibitions in July, 2016

THE ROMANS

The collection of Roman busts and portraits reminded me of the equal, though larger, collection at the Copenhagen Museum of Art. The Romans were able to carry the ancient Praxitelean portrait in marble to a greater emotionality and fidelity to the original model. Nevertheless, one cannot but feel that the portraits are idealized, and do not show all the warts. Or they portray the Emperor at the time of his youth, as in the case of the magnificent bust of the Emperor Tiberius.

When Rome became an Empire, roughly at the beginning of the so-called Common Era in World History, during and after the reign of Octavius Augustus, a cult of the Emperor was promoted, for legitimization of authority and to unify Rome’s far-flung territories and colonies. The cult of the Emperor, although premised on devotion to an institution, was also inevitably a cult of the man who occupied the office at the moment. Hence the portraits had to be flattering: it had to depict a man that you could love. Or a woman that you could fear, such as Agrippina the Elder.

Agrippina the Elder

Agrippina the Elder was the wife of Germanicus, and a member of the aristocratic family of Octavius Augustus, grand-daughter of the Emperor. The following is an excerpt from the Wikipedia article:

Her personality and conduct did however receive a certain amount of criticism. Her practice of accompanying Germanicus on campaigns was considered inappropriate, and her tendency to take command in these situations was viewed with suspicion as subversively masculine. Tacitus described her as “determined and rather excitable” - "Agrippina knew no feminine weaknesses. Intolerant of rivalry, thirsting for power, she had a man's preoccupations". Throughout her life, Agrippina always prized her descent from Augustus, upbraiding Tiberius for persecuting the blood of his predecessor; Tacitus, in writing of the occasion, believed this behavior to be part of the beginning of "the chain of events leading to Agrippina's end."

She was the first Roman woman of the Roman Empire to have traveled with her husband to Roman military campaigns; to support and live with the Roman Legions. Agrippina was the first Roman matron to have more than one child from her family to reign on the Roman throne. Apart from being the late maternal grandmother of Nero, she was the late paternal grandmother of Princess Julia Drusilla, the child of Caligula. Through Nero, Agrippina was the paternal great-grandmother of Claudia Augusta, (Nero's only child through his second marriage to Poppaea Sabina).

From the memoirs written by Agrippina the Younger, Tacitus used the memoirs to extract information regarding the family and fate of Agrippina the Elder, when Tacitus was writing The Annals. There is a surviving portrait of Agrippina the Elder in the Capitoline Museums in Rome.[Wikipedia]

Portrait bust, possibly Agrippina the Elder, Roman c. 25 A.D. White, fine-grained marble. Found at Tarentum, South Italy. Bequest of David M. Robinson, 1958

TIBERIUS

Head of Tiberius. Copy of First Century A.D. Roman sculpture. White marble. Purchased in Rome, July 1954. Bequest of David M. Robinson, 1958

OCTAVIAN

Portrait Bust of Augustus. Roman c. 350 A.D. Carrara marble. Found near Venice in 1953. Purchased by David M. Robinson, 1953. Bequest of David M. Robinson, 1958.

THE GODDESS DEMETER

Bust of Demeter. Roman, artist unknown, ca. First Century A.D. Roman copy of a

Greek original from the Fifth Century B.C.E. Asia Minor marble. Gift of Helen Tudor Robinson. Museum note: Demeter was the Greek goddess of the harvest. The holes in the ears are for earrings.

Greek original from the Fifth Century B.C.E. Asia Minor marble. Gift of Helen Tudor Robinson. Museum note: Demeter was the Greek goddess of the harvest. The holes in the ears are for earrings.

HEAD OF A PHILOSOPHER

Head of a Philosopher. Roman copy of Greek original. 250- 450 A.D.

White Parian marble. Found near

Naples, 1953. Bequest of David M.

Robinson, 1958.

Head of a Philosopher. Roman copy of Greek original. 250- 450 A.D.

White Parian marble. Found near

Naples, 1953. Bequest of David M.

Robinson, 1958.

AESCHINES, THE ORATOR

Bust of Aeschines, the Orator. Roman, artist unknown, date unknown, copy of a

Greek original, ca. 300 B.C.E., Pentelic marble. Gift of Helen Tudor Robinson. Museum note: Aeschines, an Athenian orator

and statesman, urged his fellow citizens to ally themselves with Phillip of

Macedonia rather than resist him and risk destruction.

[The destruction of Athens was inevitable. The weakness of the post-Socratic Hellas, of the Classical Ideal, therefore, is its naïve confidence and optimism, the Alexandrine optimism of all “scientists” and other species of "knowers".]

[The destruction of Athens was inevitable. The weakness of the post-Socratic Hellas, of the Classical Ideal, therefore, is its naïve confidence and optimism, the Alexandrine optimism of all “scientists” and other species of "knowers".]

MARCUS AURELIUS

Marcus Aurelius. Roman, artist unknown, late Second Century A.D. Pentelic marble. Gift of Helen Tudor Robinson.

THE COLLECTOR

David M. Robinson

David Moore Robinson (September 21, 1880, in Auburn, New York and died on January 2, 1958, in Oxford, Mississippi) He was an American Classical archaeologist, credited with the discovery of the ancienty city of Olynthus in northern Greece.

In the portrait above, Robinson is shown with one of his finds, the Greek head of a Satyr, shown below:

Satyr. Greek, from Pergamon, ca. 200 B.C.E., marble. Gift of Helen Tudor Robinson.

The following is from the Wikipedia article on David M. Robinson:

Robinson earned his A.B. (1898) and Ph.D. (1904) at the University of Chicago. Robinson served on the faculty of Johns Hopkins University (1905-1947).[3] After retirement, he moved to the Department of Classics at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, Mississippi. Many ancient objects from Robinson's collection were donated to the University of Mississippi and now constitute the David M. Robinson Memorial Collection of Greek and Roman Antiquities.[4]

In addition to the excavations at Olynthus, he participated in archaeological excavations at ancient Corinth (1902) and Sardis (1910), as well as Pisidian Antioch (1924).

Among his students (he is credited with training 75 Ph.D. recipients and 41 M.A. recipients) were George M.A. Hanfmann, Allan Chester Johnson, George E. Mylonas, Paul Augustus Clement, Jr.,[5] James Walter Graham, Mary Ross Ellingson, and William Andrew McDonald.[6]

Robinson was awarded the Cross of the Royal Order of the Phoenix by King Paul of Greece in 1957.[

Controversy

Robinson published his findings at Olynthus in a 14-volume series, Excavations at Olynthus, most of which he wrote himself. However, he has recently been charged with plagiarizing the work of his student Mary Ross Ellingson and at least three other students. It has been shown that he published Ellingson's master's thesis and doctoral dissertation in volumes VII and XIV of Excavations at Olynthus as his own work.

Publications

- 1904. Ancient Sinopea. University of Chicago (dissertation).[10]

- 1924. Sappho & Her Influence on Ancient and Modern Literature[11]

- 1930. with C. G. Harcum and J. H. Iliffe. A Catalogue of the Greek Vases in the Royal Ontario Museum of Archaeology, Toronto. Toronto: The University of Toronto Press.

- 1929-1952. David M Robinson; George E Mylonas. Excavations at Olynthus. (Johns Hopkins University studies in archaeology, no. 6, 9, 11-12, 18-20, 25-26, 31-32, 36, 38-39.) 14 v. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- 1934-1938. with S. E. Freeman and M. McGehee. The Robinson Collection, Baltimore, Md.(Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum. United States of America fasc. 4, 6-7.) Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- 1951-1953. George E. Mylonas; David M. Robinson; Doris Raymond. Studies presented to David Moore Robinson on his seventieth birthday. 2 v. Saint Louis: Washington University.

Ancient Olynthus.

Aerial view of the ancient city of Olynthos

The city today on the Chalkydic Peninsula.

David Robinson with his collection

David Robinson with his collection.

David M. Robinson with his field workers in Olynthus.

The Collection in storage.

Helen Tudor Robinson, resting in the ruins of Olynthus.

THE GREEKS

The Horos stone (below) is a record of a property transaction and physical evidence for the determination of the boundaries of the estate. The Horos stone also includes information on the parties to the contract, and the price paid on the mortgage. It was as permanent a record as could be fashioned in the Fourth Century BCE, the century of the Peloponnesian Wars.

HEAD OF APHRODITE

Bust of Aphrodite. Greek, artist unknown, large grained island marble. Second Century A.D. Gift of Helen Tudor Robinson. Museum note: Eyes and hair are “melting” style typically Praxitelean. The holes in the ear lobes are for earrings. The hair was created with a running drill. Likely early Antonine Dynasty.

HEAD OF A COMIC ACTOR

Head of Comic Actor Sculpture. Roman. First Century A.D. Theater of Tuscolo Hill, Tusculum. Carrara marble. Purchased by David Robinson, 1954. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frank S. Peddle, Jr. Museum note: This Roman actor is in costume, wearing a typical theater mask and wig. The deep set eyes were once embedded with precious stones. The hair is carved in the style of a wig; big curls atop the head that end in braids. The back of the sculpture is plain and rough, suggesting it was placed against a wall or in a niche where the marble would show best. The sculpture contains large cracks. The sculptural head was purchased by David Robinson in the early 1950’s. He believed that it was from Tusculum, home to Cicero. Recorded excavations first begun at this site in 1806 by Lucien Bonaparte. Since then several additional excavations have occurred.

There are several accounts of the Spartan common mess, the Sisytia, where the male Spartan citizens, the homoioi, or 'equals' eat their meals together. During the meal, a Helot (slave) would be brought in and given too much to drink. The Helot would then degrade himself and shuffle about, as the Spartans mocked him. The masks used for the Helots in these sadistic demonstrations resembled the face of the Comic Actor above.

GREEK CERAMICS

Attic Red-Figure ceramics

The Attic red-figure style appeared rather suddenly

in Athens around the year 530 BCE. It shows a tendency towards the naturalistic

which is made possible by changes in technique. The figures are outlined, and

the inner details are shown by thin lines of paint. This is similar to

contemporary painted panels, but the black background and the lack of any other

colors must have been the vase painters' own idea. As well, major lines are

emphasized by the use of a thicker and more viscous solution on the black paint

so that they stand out in relief. The overall effect is one of greater

naturalism and grace.

Neck amphora in Attic Red-Figure style, 470 BCE, shows Triptolemos on a winged chariot.

In the red-figure style, figures are drawn in rather

than engraved. Red-figure painting made it possible for the artist to convey a

more naturalistic picture of human anatomy. In the last ten years of the sixth

century BCE, vase painters working in red-figure style abandoned the ancient

tradition of composing figures in strictly profile or frontal views. This was

followed by a new anatomical system which placed this style within the

tradition that has come to be known as Classical, characterized by anatomical

verisimilitude, naturalistic expressions and movements, and flowing drapery and

garments that hang naturally on the body of the human figures.

The eye, for example, until almost the end of the sixth century, had always been shown frontally, with the eyeball in the center (see the Athena holding a helmet, below), even if the face was in profile. In red-figure style, the eyeball moves forward and the eye begins to open in front and is shortened to a correct profile view. As well, the drapery changes from a decorative to a more natural system of folds. Scenes of human life become more common, especially the convivial and the athletic, but even in such scenes, vigorous activity becomes less common than it was in the earlier black-figure style.

The eye, for example, until almost the end of the sixth century, had always been shown frontally, with the eyeball in the center (see the Athena holding a helmet, below), even if the face was in profile. In red-figure style, the eyeball moves forward and the eye begins to open in front and is shortened to a correct profile view. As well, the drapery changes from a decorative to a more natural system of folds. Scenes of human life become more common, especially the convivial and the athletic, but even in such scenes, vigorous activity becomes less common than it was in the earlier black-figure style.

OLD SATYR PURSUING A MAIDEN

Red-figure Attic krater from the Fifth Century.

And old satyr pursues a young maiden. Satyrs were inferior mythical beings

"demons" of Greek mythology (spirits of mountains and forests), which

the Poetry and Art depicts them from the waist up almost anthropomorphic, bald

and pointy ears, legs and tail with goat hooves and features.

The object of pursuit.

ART IN THE COLONIES

When red-figure ceramics display a variety of colors, including white, in the rendition of the figures, the object is most likely from the colonies, particularly the Southern Italian colonies.

STATUETTE OF PAN

Statuette of Pan. 400 – 425 B.C.E. Bronze. Gift of Helen Tudor Robinson. Museum note: Pan was half man half goat god of shepherds game animals like hares and rabbits and small birds.

[But that’s not all Pan was. Many years after all of the Mediterranean had become Christian, it is said that a ship sailed by one of the Ionian Islands, probably Zakynthos, and the sailors could hear a long shout from the shore, almost a wail, “The great god Pan is dead! The great god Pan is dead!” Why did they feel the need to proclaim this fact to the world? To a world that already knew that all the old gods were dead. Maybe they simply wanted to calm the sailors. Pan was “panic,” a thrill of fear and erotic force which spreads through the forests of Arcadia on summer afternoons, at mid-day, when the fauns rest. That erotic force is a panic, for there is also fear in it: fear of the wildness of the elemental natural procreative forces and also fear of self-abandonment and self-oblivion. An anticipation of danger is panic, but we panic over many things. It is irrational fear.]

HEPHAISTOS ON HIS MULE

Calyx Krater, 470-460 B.C.E. Attic Red-figure style. A. Hephaestus on a mule; satyr playing the flute b. Satyr pursuing a maenad. By the Atamura Painter. Gift of Helen Tudor Robinson. Museum note: Hephaestus was the god of the smiths and craftsmen. He quarreled with his mother Hera, was exiled from Mount Olympus and later, when the gods needed his services, refused to return. He would not yield to force or reason, but Dionysos gave him plenty of wine and persuaded him to go back. Being lame in one leg, Hephaestus rode a mule for the return trip.

The myth of Hephaistos and his mule, returning to Olympus drunk, in the company of Dionysos or one the god's heralds, seems to me to mean that Hephaistos had to get drunk in order to be able to bear the company and society of the other gods. Hephaistos was a smith and a metal craftsman, and he was responsible for providing the gods with armaments and jewelry and other highly valued objects. He is therefore an immensely powerful god in the Greek Pantheon. But he is also a worker-god, a rather taciturn, busy, aloof and silent god. Velazquez portrays him very well in his painting of Apollo's visit to the forge.

Velazaquez, 'Apollo at the Forge of Vulcan'

The satyr is tumescent. The god Dionysus is not only the god of wine and vine, but also the god of orgiastic sexual festivals wherein the self is lost in the turmoil and oblivion of the orgy, and of the orgasm. The Dionysiac is the utmost affirmation of the natural human life.

MOSAIC OF ACHILLES AND HIS MOTHER

THE MATRONS OF ATHENS

Lebes Gamikos. Attic red-figure 450-440 BCE: Bride

seated receiving gifts and shown on the reverse side with attendants and a

mirror.

The Lebes Gamikos, literally meaning “nuptial vase” (plural - lebetes gamikoi) is a form of ancient Greek Pottery used primarily in marriage ceremonies, probably in the ritual sprinkling of the bride with water before the wedding. In form, it has a large bowl-like body and a stand that can be long or short. Painted scenes are placed on either the body of the vessel or the stand. Below are two images of the stand of the vase depicted above. It shows the hero Perseus pursuing the nymph Thetis. The classical style is evident in the representation of the eye, the graceful depiction of the movement of the limbs and the naturalness of the draped garment.

The Lebes Gamikos, literally meaning “nuptial vase” (plural - lebetes gamikoi) is a form of ancient Greek Pottery used primarily in marriage ceremonies, probably in the ritual sprinkling of the bride with water before the wedding. In form, it has a large bowl-like body and a stand that can be long or short. Painted scenes are placed on either the body of the vessel or the stand. Below are two images of the stand of the vase depicted above. It shows the hero Perseus pursuing the nymph Thetis. The classical style is evident in the representation of the eye, the graceful depiction of the movement of the limbs and the naturalness of the draped garment.

The more naturalistic representation of the eye and eyeball in Attic red-figure style is evident in the figure of the bride below, both upon her receipt of a gift and as she looks at herself in the mirror, in the Lebes Gamikos of 450-440 BCE.

Lebes Gamikos. Attic red-figure 450-440 BCE: Perseus

pursuing Thetis (detail on stem)

Lebes Gamikos. Attic red-figure 450-440 BCE: Perseus

pursuing Thetis (detail on stem)

Lebes Gamikos. Attic red-figure 450-440 BCE: Perseus

pursuing Thetis (detail on stem)

THE MAENAD KYLIX

Ease of movement and grace in action are evident in

the representation of a Dyonisiac Maenad holding a thyrsos, the staff made of

giant fennel stalks carried by the Bacchiadae, and a snake on her right arm,

below:

Kylix. Attic red-figure 490-80 BCE: Maenad with

thyrsos and snake.

Note that the eyeball of the maenad has moved

forward in this representation, compared to the Athena directly above. As well,

the garment flows more naturally and hangs gracefully from the outline of the

thigh and left knee.

PALLAS ATHENA GAZING ON A SOLDIER'S HELMET

The Goddess Pallas Athena holding a helmet over an altar. Amphora, Attic red-figure style. 500-490 B.C.E.

The goddess of intelligence, cunning and wisdom, stares at a soldier's helmet, perhaps that of one of her favorite mortals, like Odysseus, or Achilles. Is war necessary for intelligence? Does intelligence thrive on war? Is it cunning to worship war among mortals? These are some of the questions raised by this representation. A cock is painted above the scene, shown on the upper right of the photograph.

The cock of battle. The gift that the erastes gave to the family of the eromenos, when he went courting. The cock, the helmet, and wisdom. Perhaps war was an intelligent option in the small city-states of Greece, walled hamlets (except for Sparta, which needed no walls!), with rates of population growth sustained by the degree to which they could keep their hostile neighbors and marauding bands from depleting their cultivated lands and flocks. It is not the same in a complex urban and developed society like ours, the existence of which is almost automatic and depends on complex and fragile systems of communication. The flesh on flesh wars of the past have become unnecessary.

No comments:

Post a Comment