The images shown below are photographs I took at the University of Mississippi Museum of Art in July, 2011, a few examples of black-figure and red-figure Attic pottery which are works of Athenian craftsmen from the sixth and fifth centuries BCE and part of the permanent collection there. There are only a few pieces depicted in the blog, but they reveal the main characteristics of each style. As well, I show a few oil lamps, and the painting on a kylix which reveals an unusual method of depilation by means of the oil lamp.

[to enhance the size of the photos right click on them and open in new window]

Pallas Athena holding a helmet over an altar.

Amphora, Attic red-figure style, 500-490 BCE.

David M. Robinson was born in Auburn, New York, in 1880. He received his A.B. degree in 1898 and his Ph.D. in 1904 from the University of Chicago. After serving as head of the Classics Department at Illinois College in Urbana from 1904-05, Robinson spent the majority of his career at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Considered an influential figure in Mississippi Archaeology, Robinson conducted artifact excavations in Corinth, Greece (1902-1903) and in Sardis, also in Greece in 1910. In 1924, he directed the excavation of Pisidian Antioch and Sizma for the University of Michigan. His greatest archaeological achievement was the discovery and excavation of the ancient city of Olynthus from 1928 through 1938. Throughout his career, Robinson was widely published in Archaeology as well as Greek and Roman literature, history and linguistics.

In 1947, he retired from Johns Hopkins and accepted a position as Professor of Classical Archaeology at the University of Mississippi where he taught for ten years. Robinson passed away in 1958, leaving behind a wealth of published research and a unique collection of Greek and Roman antiquities, which was donated to the University of Mississippi Museum of Art. (Source: Museum notes)

Considered an influential figure in Mississippi Archaeology, Robinson conducted artifact excavations in Corinth, Greece (1902-1903) and in Sardis, also in Greece in 1910. In 1924, he directed the excavation of Pisidian Antioch and Sizma for the University of Michigan. His greatest archaeological achievement was the discovery and excavation of the ancient city of Olynthus from 1928 through 1938. Throughout his career, Robinson was widely published in Archaeology as well as Greek and Roman literature, history and linguistics.

In 1947, he retired from Johns Hopkins and accepted a position as Professor of Classical Archaeology at the University of Mississippi where he taught for ten years. Robinson passed away in 1958, leaving behind a wealth of published research and a unique collection of Greek and Roman antiquities, which was donated to the University of Mississippi Museum of Art. (Source: Museum notes)

Satyr, visible in the portrait of David Robinson, is a marble Greek bust from Pergamon, dated ca. 200 BCE, part of Robinson's private collection.

Attic Black-Figure Ceramics

Attic black-figure style emerged from the Proto-Attic style, towards the beginning of the seventh century BCE. It is a reflection of the Archaic or Lyric Art of the Greeks, primarily the style of the sixth century BCE. (See my blog of October 31, 2010: "Tragic Art: The Treasure House of the Siphnians.") A new method of outline drawing developed, with extensive use of white and an occasional but inconsistent admixture of incisions. Human figures are presented on a large scale, etched against a white or red background, or against the background of the warm brown of the clay. The figures are always shown frontally or in profile and in rigid pose. The representations are one-dimensional, formalized and stiff, in the form of religious imaging. Towards the year 630 BCE, the discipline of the Corinthian school begins to be emulated and a fully developed Archaic art of ceramics becomes prevalent in the Attic peninsula until the end of the sixth century BCE, when it is displaced by red-figure style (discussed below). Around 530 BCE, the inadequacy of the black-figure method of silhouette and incision will lead to the introduction of red-figure outline drawing. Yet the black-figure style did not die off immediately and works in this style are still being made in the fifth century. Due to the conservatism of the priestly classes and the ruling elites, the black-figure style was required on the amphoras presented full of oil to the victors in the Panathenaic Games.

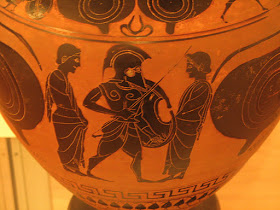

I photographed only two examples of the black-figure style from the David Robinson Collection. The first is the neck-amphora of 530-515 BCE showing a warrior and two youths.

I photographed only two examples of the black-figure style from the David Robinson Collection. The first is the neck-amphora of 530-515 BCE showing a warrior and two youths.

Neck-amphora. Attic Black-Figure Style, 530-515 BCE.

Note that the warrior and the two youths are depicted in profile and entirely in silhouette, in one-dimensional fashion, rigidly and formally facing one another. Their eyes are in profile and the eyeballs in the center of the eye, as was the formal tradition of this style. The garments, as well as the pose, are formally stylized; the line etchings are fine and crisp.

The oldest piece portrayed here is an Attic black figure Skyphos in the Boeotian style from the Fifth century BCE, which satirizes Circe and Odysseus. The figures depict a comic satire in the form of caricatures designed for comedic purpose. Circe stands above Odysseus who is receiving a gift from her.

Attic Red-Figure ceramics

The Attic red-figure style appeared rather suddenly in Athens around the year 530 BCE. It shows a tendency towards the naturalistic which is made possible by changes in technique. The figures are outlined, and the inner details are shown by thin lines of paint. This is similar to contemporary painted panels, but the black background and the lack of any other colors must have been the vase painters' own idea. As well, major lines are emphasized by the use of a thicker and more viscous solution on the black paint so that they stand out in relief. The overall effect is one of greater naturalism and grace.

Neck amphora in Attic Red-Figure style, 470 BCE, shows Triptolemos on a winged chariot.

In the red-figure style, figures are drawn in rather than engraved. Red-figure painting made it possible for the artist to convey a more naturalistic picture of human anatomy. In the last ten years of the sixth century BCE, vase painters working in red-figure style abandoned the ancient tradition of composing figures in strictly profile or frontal views. This was followed by a new anatomical system which placed this style within the tradition that has come to be known as Classical, characterized by anatomical verisimilitude, naturalistic expressions and movements, and flowing drapery and garments that hang naturally on the body of the human figures. The eye, for example, until almost the end of the sixth century, had always been shown frontally, with the eyeball in the center (see the Athena holding a helmet, below), even if the face was in profile. In red-figure style, the eyeball moves forward and the eye begins to open in front and is shortened to a correct profile view. As well, the drapery changes from a decorative to a more natural system of folds. Scenes of human life become more common, especially the convivial and the athletic, but even in such scenes, vigorous activity becomes less common than it was in the earlier black-figure style.

Amphora in Attic red-figure style, 500-490 BCE: Athena holding a helmet over an altar

Ease of movement and grace in action are evident in the representation of a Dyonisiac Maenad holding a thyrsos, the staff made of giant fennel stalks carried by the Bacchiadae, and a snake on her right arm, below:

Kylix. Attic red-figure 490-80 BCE: Maenad with thyrsos and snake.

Note that the eyeball of the maenad has moved forward in this representation, compared to the Athena directly above. As well, the garment flows more naturally and hangs gracefully from the outline of the thigh and left knee.

Kylix. Attic red-figure 490-80 BCE: Maenad with thyrsos and snake.

[enhance viewing of the photos by right-clicking on the image and opening link in new window]

Lebes Gamikos. Attic red-figure 450-440 BCE: Bride seated receiving gifts and shown on the reverse side with attendants and a mirror.

The Lebes Gamikos, literally meaning “nuptial vase” (plural - lebetes gamikoi) is a form of ancient Greek Pottery used primarily in marriage ceremonies, probably in the ritual sprinkling of the bride with water before the wedding. In form, it has a large bowl-like body and a stand that can be long or short. Painted scenes are placed on either the body of the vessel or the stand. Below are two images of the stand of the vase depicted above. It shows the hero Perseus pursuing the nymph Thetis. The classical style is evident in the representation of the eye, the graceful depiction of the movement of the limbs and the naturalness of the draped garment.

Lebes Gamikos. Attic red-figure 450-440 BCE: Perseus pursuing Thetis (detail on stem)

Oil Lamps

Oil Lamps were not only used for light but also served as votive offerings in sanctuaries and also as tomb furniture. Lamp forms are highly varied, ranging from simple to elaborate. Lamps used in ancient Greece could sit on stands or be suspended from cords or chains. Olive oil was a popular fuel and a wick would be placed in the lamp and out the nozzle to ensure even burning. Lamps from Athens changed around the VIIth. century BCE, with more shallow lamps and longer nozzles being made in molds. This popular form was the standard for thousands of years. Larger and more decorative lamps were specialty items and usually denote ceremonial status. (Source: Museum notes)

Kylix depicting a woman removing her pubic hair by burning it with an oil lamp.

Oil lamps were also used for personal hygiene. On this Kylix (drinking cup), a woman is shown holding an oil lamp near her pubic region just close enough to singe the hair as she squats over a water basin with a sponge in her right hand as a precautionary measure. This practice was common for pubic depilation in Greece and its depiction on Grecian art is extremely rare. (Source: Museum notes).

No comments:

Post a Comment